The Dreams of an 18-Year-Old Migrant Worker

Ibrahim wants to earn more money, get a better job, and have a family, but the COVID-19 pandemic has made his goals harder to achieve.

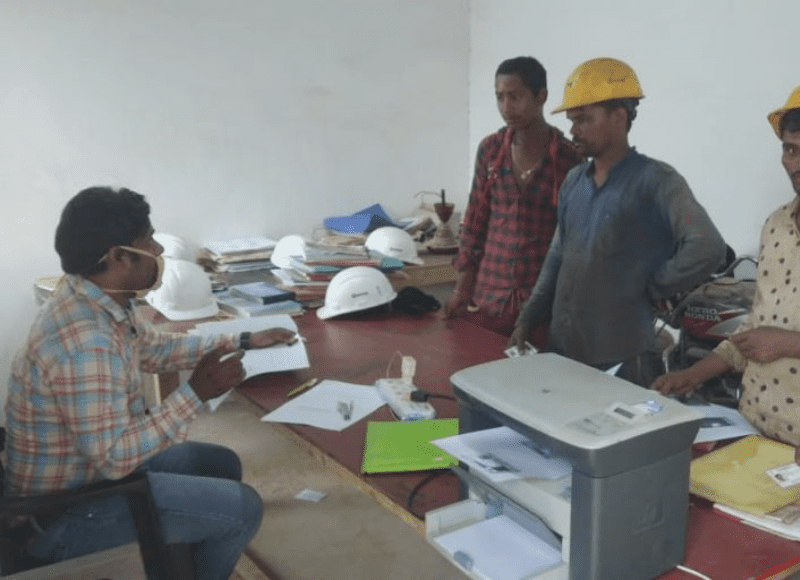

Eldest of 8 siblings, Ibrahim moved from his hometown in Kathiya district in Bihar to Delhi, in February 2020. Fresh out of high school, he migrated to the big city hoping to earn money to supplement the income of his father, who works as a daily wager in Bihar. Soon after he managed to find a job as a construction worker at a site in Gurgaon, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and all construction activities were banned. Ibrahim, who was then barely 17, was thrown into unprecedented uncertainty. “We faced a lot of issues at that time. There was no work. Everything became costly. Food was an issue. After the lockdown, I lost work and had to go back home in a truck. It took me 6-7 days to reach home. I had no work or source of income for 3-4 months,” recounted Ibrahim.

When he finally managed to return to his hometown, he realised that his situation was not unique. “People around me had similar experiences. My father also wasn’t called for work. Money was tight,” said Ibrahim. After 4 months, he finally returned to Haryana to resume work at the construction site. He typically works 8-hours a day doing hard labour, but worries if working this job and hoping the situation will improve is enough. “I want to earn more money, get a better job, get married and have a family. But I’m the only earning member in my family now, so I’m not sure if I’ll be able to achieve these goals,” said Ibrahim.

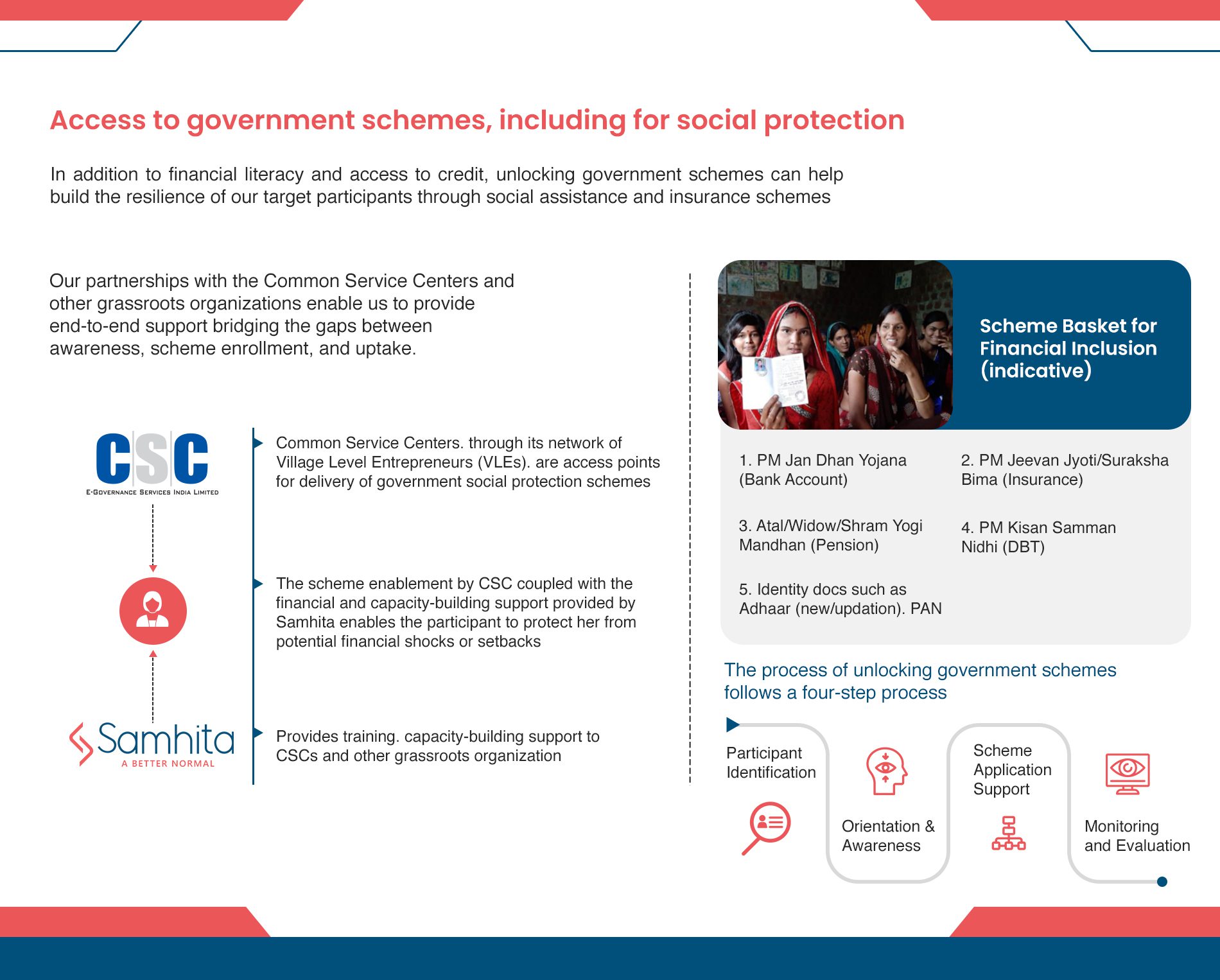

Even though he had been working for over a year, Ibrahim didn’t have a bank account. He had heard about the government’s Jan Dhan Yojana but had no idea how to go about opening an account under the scheme. In February 2021, when a social protection scheme linkages camp for construction workers was conducted by the REVIVE Alliance, he understood the details of the scheme for the first time and realised the value of a zero-balance account.

“The documentation process was easy. I got a PAN card and Jan Dhan account. I think this will be very beneficial in the long-run — I keep money in the bank account and can use the PAN card to get my KYC (Know Your Customer) done,” said Ibrahim, who is glad to have his salary now credited to his bank account directly.

With the support of REVIVE, Ibrahim is now part of the formal banking system. This will ensure he has access to financial services, and timely, adequate and low-cost credit when required. It will also contribute to helping this 18-year-old work towards his goals with greater support and resilience.